What constitutes the musical mainstream, and what’s upstream of that? Who determines what fits into musical categories, into genre streams that guide musicians in their careers, presenters in their programming choices and listeners in their concertgoing? Which music is a legitimate representation of a lineage worth investigating, and what is a marginal, outsider expression?

What constitutes the musical mainstream, and what’s upstream of that? Who determines what fits into musical categories, into genre streams that guide musicians in their careers, presenters in their programming choices and listeners in their concertgoing? Which music is a legitimate representation of a lineage worth investigating, and what is a marginal, outsider expression?

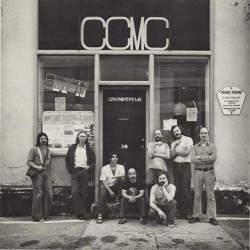

The Music Gallery (I’m tagging it MG in this story) founded in 1976 by Peter Anson and Al Mattes of the free-improvising group CCMC – originally an acronym for Canadian Creative Music Collective – is a constantly morphing downtown music institution that has valiantly grappled for decades with these and other thorny questions to do with music presentation. During that time it has variously been a venue for rent, a producer and co-presenter, a cultural hub, a rehearsal space and concert home for numerous musicians and ensembles of multiple genre affiliations, an exhibition space for visual art, the home of a record label, and Musicworks magazine’s original incubator.

Had it been situated in Soho, NYC it might have been long ago widely recognized as a key downtown music institution. In Toronto, though terra incognita to most residents, it nevertheless remains a vital venue for edgy performers and adventurous music seekers alike.

The Music Gallery in the 1970s

Before going further I should state my personal interest: over the years I’ve been involved in the MG in various capacities. During its earliest years, as an emerging musician, composer, ensemble leader and as editor of Musicworks, I often hung around its first location, the loft-ish 30 St. Patrick St. just north of Queen St. I hobnobbed and jammed – mostly on bassoon and piano at the time – with local and visiting musicians I discovered there and grew to admire, among them American jazz trumpeter Don Cherry and Dutch pianist and composer Misha Mengelberg. Toronto drummer Larry Dubin (1931-1978), to my mind the person who most clearly exemplified the foundational CCMC group aesthetic, was often in the house practising with whomever dropped in during the day. For a while he had a sign on the exposed foam-covered wall on a piece of cardboard, its casual handwritten scrawl belying the potency of its message. “No Tunes Allowed” it read, a message which still conveys a sense of the rigour of his aesthetic convictions, an intense iconoclastic artistic dedication.

From afternoon jam sessions with Larry I attended, I recall saxists John Oswald and Nobuo Kubota, pianists Michael Snow and Casey Sokol, bassist Al Mattes and many others adding their voices. It was a lively, generous, open-spirited free music scene.

What was a typical couple of weeks of concerts like at the MG in the 1970s and 1980s? A bricoleur’s view would have audiences listening to post-bop free jazz one night, an interspecies ensemble the next, followed on the weekend by a concert of open-form electroacoustic works accompanied by modern dance, or perhaps Carnatic music. The next week local and visiting modernist and postmodernist concert music composers like James Tenney, Udo Kasemets, Iannis Xenakis, John Cage, David Rosenboom, Pauline Oliveros and dozens of others might lecture, rehearse or lead ensemble renditions of their works. Later in the evening when all was dark and quiet, the Glass Orchestra might light a few dozen tea candles, and, during the course of their generally gentle vitreous music, break a few oversized brandy snifters, their shards tinkling in the candlelight.

Often young Toronto musicians toeing one musical edge or another made the MG the proving ground for their early gigs. Until 1980 it even had a record label, Music Gallery Editions run by Marvin Green, which in just a few ambitious years released 33 LPs – an esoteric blend of the experimental and vernacular. And each Tuesday night, regular as clockwork, CCMC the resident house band fearlessly explored free improvisation: music in which form evolved organically and process was king. There was one firm rule, however: all MG concerts were recorded. The audio tapes from the first two decades survive, archived at York University, where a digitization project has begun.

The Music Gallery Today: David Dacks, AD

That was then. To delve deeper into what the MG is today, I approached David Dacks, its artistic director since January 2012. I met Dacks at the MG booth at the INTERsection “New Music Marathon and Musicircus” staged at Yonge-Dundas Square on September 6. Curious passersby one after another found their way to the Music Gallery table on the south side of the square where Dacks (the webzine Foxy Digitalis called him “downright affable”) and MG executive director Monica Pearce genially guided potential audiences though their inquiries about the MG.

That was then. To delve deeper into what the MG is today, I approached David Dacks, its artistic director since January 2012. I met Dacks at the MG booth at the INTERsection “New Music Marathon and Musicircus” staged at Yonge-Dundas Square on September 6. Curious passersby one after another found their way to the Music Gallery table on the south side of the square where Dacks (the webzine Foxy Digitalis called him “downright affable”) and MG executive director Monica Pearce genially guided potential audiences though their inquiries about the MG.

Seeking more background on his curatorial approach, I phoned Dacks at his office on September 12. The more we spoke, the more apparent was his intimate familiarity with a wide swath of transnational musical geography. I was aware of his music journalism energizing magazines such as Exclaim! and Musicworks, but not so aware of his music career pre-MG. “I have over two decades of experience as a DJ, music programmer, broadcaster and journalist,” said Dacks. “In 2011 I served on the grand jury for the Polaris Music Prize and for ten years hosted ‘The Abstract Index,’ a community forum for new ideas in music on CIUT FM.”

Asked about today’s MG audience, he says that they are generally “curious about music and the cultures that make [it]. They appreciate musical virtuosity, whether it be in the form of well-textured noise, a performance by a [West African] griot, or [embracing] a sacred, or experimental” approach. Dacks sees a healthy “increase in the MG’s audience, an upswing, over the last few years … and there’s potential for further growth as subway connections to York University and further afield are completed.”

How does he define his curatorial aims? “I believe in music programming which possesses multiple points of interest, and is not necessarily confrontational, but rather fosters a community-building environment.”

How does his approach differ from that of his predecessor, Jonathan Bunce, who put his distinctive brand on the MG from 2002 to 2011? “Jonny had different musical tastes [from mine],” Dacks says. “They emerged organically from his punk roots,” roots which nurtured Bunce’s rebellious instincts. “Jonny proposed pop music as a legitimate form of artistic expression, as well as establishing such music streams at the MG as pop, jazz, world, experimental,” all categories useful in fundraising, programming, packaging and promoting concerts. They reflected prevailing commercial market models, yet gave programmers and single-genre curators a clear and useful framework within which to present concerts at the MG over the last decade.

By comparison, Dacks’ background as a club DJ and in radio (he began at CIUT in 1986) gave him an outlook which encourages “synthesis, multiple affiliations and opportunities for [genre] fluidity in music. My work in DJ culture is rooted in [creating] interesting music mixes and Jamaican dub.”

Dacks’ keystone MG fall concert-and-critical-conversation series is titled “X Avant.” Now in its ninth season, there’s plenty of opportunity there to explore such genre fluidity, and his theme “Transculturalism: Moving Beyond Multiculturalism”underscores that fact.

“But what does that mean exactly?” I ask. “At its heart,” Dacks says, “it is a challenge to expectations about culturally defined music.”

Dacks goes on to talk about a pivotal 2004 WOMEX award acceptance speech by Marc Hollander, who in Dacks’ words, aimed to “get away from definitions which were starkly dualistic.” The founder of the boundary-breaking and successful independent Belgian label Crammed Discs, Hollander used the metaphor of a “meadow, not ghetto” to illustrate his label’s “pathologically eclectic” music mix. “Instead of multiculturalism (where each group retreats in its little enclosure),” Hollander said, “let’s have more inter- or transculturalism ... more mixtures.”

Dacks’ X Avant 2014 theme builds on the MG’s (and Toronto’s) reputation since the 1970s as a seedbed for such cultural multiplicity and emerging hybridity. It also emphasizes another over-arching MG goal –to ensure that its concerts are affordable. “We made the X Avant festival pass only $40 for five shows, wanting to ensure a low barrier to entry,” a chuffed Dacks points out.

Looking ahead

What’s in store for 2015/16, the MG’s 40th anniversary season? Well, one new direction will be to “eliminate music genre streams. We feel that this reflects how people consume music today,” said Dacks, echoing the venue’s response to the general trend of “fewer CDs, but more YouTube and streaming audio being consumed.” Perhaps there’s also an echo here of his DJ background, in which the immense database comprised of all recorded musics over the last 125 years – the field or meadow, if you wish – can theoretically be re-heard, sampled, sequenced, superimposed and mechanically and/or electronically altered in live performance for an audience.

Is the MG “upstream” from “the mainstream?” Perhaps it doesn’t matter much in the end. Yet I can’t help wondering, two generations on, if the incipient de-genrefication of its music programming as articulated by its present AD is not so much ahead of its time as in some ways a return to, or at least a reverberation of, the Music Gallery’s foundational ethos.

Andrew Timar is a Toronto musician and music writer. He can be contacted at worldmusic@thewholenote.com.