Jörn Weisbrodt, 41, is the third part of the German trifecta that is moving and shaking the arts in Toronto. In 2011, he was appointed the artistic director of the Luminato Festival, and thus joins the Canadian Opera Company’s general director, Alexander Neef, and music director, Johannes Debus, as a member of the wunderkind generation of Young Turk Germans making a splash on the worldwide culture scene. (The Neef/Debus Q&A was in last month’s WholeNote.)

Jörn Weisbrodt, 41, is the third part of the German trifecta that is moving and shaking the arts in Toronto. In 2011, he was appointed the artistic director of the Luminato Festival, and thus joins the Canadian Opera Company’s general director, Alexander Neef, and music director, Johannes Debus, as a member of the wunderkind generation of Young Turk Germans making a splash on the worldwide culture scene. (The Neef/Debus Q&A was in last month’s WholeNote.)

When the Weisbrodt/Luminato announcement was made, every news story mentioned the fact that his life partner was Canadian/American superstar, singer-songwriter Rufus Wainwright. (The couple’s 2012 New York celebrity wedding had huge coverage in the international press.) One does not, however, become head honcho of one of North America’s leading festivals of arts and culture by being “husband of.”

What follows is an in-depth conversation with Weisbrodt that gives a perspective on his life history and the life skills that brought him to Luminato.

Tell me about your background. I was born in Hamburg, and I’d describe my life as a typical middle class tapestry. My dad was head of logistics at Unilever and my mother was a housewife. My brother is an engineer with Lufthansa. Instead of going into the army for mandatory conscription after high school, I opted for social service instead. I worked for 15 months in an operating theatre dressing the doctors and nurses, positioning the patients and getting all the equipment together, making sure everything was sterile. I’ve been a great defender of compulsory social service for young people ever since.

How did you get hooked on the arts? Hamburg is a culturally savvy town, and my parents were cultured people who went to theatre and opera. I had a musical education – I was in a boys’ choir and I studied piano. When I was older, I attended the theatre, opera or a concert four or five times a week. At university I started studying bio sciences, but I missed the culture scene. I switched to opera directing, and spent the next five years getting my undergraduate and graduate diplomas at the Hanns Eisler Music Conservatory in Berlin. My first two heroes were choreographer-director Ruth Berghaus and dramatist-theatre director Heiner Müller.

And legendary, avant-garde, American theatre and opera director Robert Wilson was your third hero. For me, Bob invented a new theatre language. In 1990, his production of The Black Rider premiered in Hamburg. Tom Waits wrote the music and William S. Burroughs the text. I was so thrilled about the production that I wrote Wilson a letter, and I got an answer. He was always interested in young people.

The Salzburg internships were important experiences while you were still a student, particularly because of Robert Wilson. I worked on two acclaimed productions. I was an intern in 1997 with director Peter Stein’s opera production of Wozzeck at the Salzburg Easter Festival. For the 1997 Salzburg Summer Festival, I became Robert Wilson’s personal assistant on Pelléas and Mélisande. He likes to recruit interns.

The following summer you worked with Wilson again, and it changed the direction of your career. It was at his Watermill Center at Southampton, Long Island where Bob supports the development of cross-disciplinary works. Being there allowed me to learn to be an enabler. I could see my career lay with being an administrator rather than being an artist, Without Bob’s influence, I could have ended up as a mediocre, second tier opera director somewhere.

The following summer you worked with Wilson again, and it changed the direction of your career. It was at his Watermill Center at Southampton, Long Island where Bob supports the development of cross-disciplinary works. Being there allowed me to learn to be an enabler. I could see my career lay with being an administrator rather than being an artist, Without Bob’s influence, I could have ended up as a mediocre, second tier opera director somewhere.

What did you do after you graduated? I signed a contract as an assistant director at the Deutsches Theater in Berlin – the theatre that director Max Reinhardt made famous. The position was going to start in a year. In between I was an intern at McKinsey and Company, a business consulting firm. If I was ultimately going to be an arts administrator, I had to learn something about business which is not a part of arts education. McKinsey actually offered me a job, so I got out of my contract at the Deutsches Theater. I knew that being an assistant director was not what I wanted.

But an arts admin job did present itself. Artistic director Peter Mussbach of the Staatsoper Unter den Linden in Berlin was opening up a second performing space. I got a job as artistic production director which involved programming and producing with the emphasis on interdisciplinary works. I also got to travel to find productions for the space. I was there for five years.

After which you joined up with Wilson again and moved to New York. I was executive director for RW Work Ltd., the company that acts as the manager and agent for Bob’s work. I was also director of the Watermill Center where I oversaw the launch of artistic residencies for an international array of emerging artists. I was responsible for the artistic vision and presentation.

How did you get to Luminato? I first met Luminato CEO Janice Price and founding artistic director Chris Lorway in 2007 to discuss the revival of Bob’s 1992 production of Philip Glass’ opera Einstein on the Beach. Luminato became one of the five partners who funded the production. At the same time, I heard that Chris was going to leave Luminato and I decided to put my name into the mix. I got my references together and handed in a vision statement. That got me to the short list of two. Hurricane Irene happened when I was supposed to go for my interview, so I ended up driving to Toronto because I couldn’t fly. The other candidate didn’t arrive. I guess he didn’t consider driving.

Why did you go after the Luminato job? I really wanted the position because my goal was to be an artistic director of a festival or a theatre. What really attracted me to Luminato was the breadth of the disciplines that the festival covered – even magic and food. It was like seven or eight mini-festivals under one umbrella. The programming also touched on the political and social scenes. The Luminato mandate seemed to be connecting people to issues through the arts, and that appealed to me.

How do you define your vision? I dream about generating new works because I believe that festivals should be the birthplace of something new – a temporary home for artists. So the first step is creating great art. We also have to get the city to give itself up to culture. We have to open up to the local arts community. In fact, Luminato has to open up to the world. We have to think in dialogues. Luminato could be one of the greatest festivals in the world if we were a creative force that brought people together. We have to create a craving for an overall experience. We want a festival community. We want to be a family. Toronto is such a multicultural city that we should be bringing cultures together – but we’re not there yet.

In what ways could the city and the festival be linked? What if we had a magician doing his show in the lobby of TIFF, and then people going to see a film would stumble on the performance? This widens the scope of the magic art form because it doesn’t have to be in a theatre. It’s also a direct connection between artist and audience.

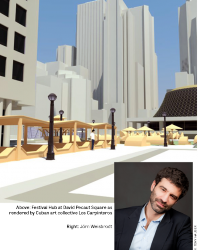

You’ve been in the job for a couple of years now. Luminato itself is just getting to its eighth season so still could be considered young. What new insights have you gathered? In this kind of business, it takes time to develop a product and get to know the city. I’ve discovered that it’s not “what” but “how” – in other words, not “what” you program, but “how” you put things together. I still believe in the multidisciplinary nature of the festival which is what attracted me in the first place. For example, the free events at the Hub in David Pecaut Square used to be just various forms of pop music. Now there is classical music, film and dance at the Hub. If you look at the Luminato program, many shows appear under several categories. I want to blur the boundaries between the disciplines.

Multidisciplinary is such an important word to you. Can you give me a concrete example of what you mean? Look at what we did in 2012. While pianist Stewart Goodyear was playing all of Beethoven’s 32 sonatas in one day, Indonesian dancer Melati Suryodarmo was performing her interpretation of the music on the same stage. In conjunction with Goodyear’s music marathon, the Royal Ontario Museum mounted an exhibit of visual artist Jorinde Voigt’s paintings inspired by each sonata. We also had a pre-concert lecture by esteemed neuroscientist and neurologist, Dr. Antonio Damasio, on music and the brain. This merger of the visual arts, dance, music and science opened up our eyes to the different ways we can look at the same thing. It also opened our ears to a deeper appreciation of the music.

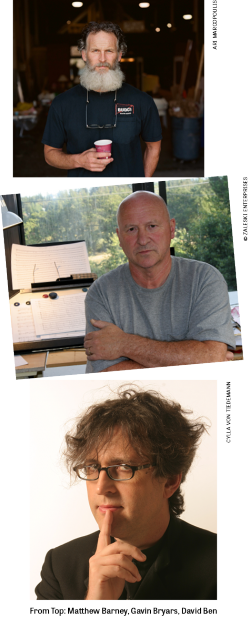

What about an example from Luminato 2014? I’ll give you two. The revolutionary American visual artist-filmmaker Matthew Barney is getting a multifaceted approach. Collectively, it’s a complete view of Barney. He’s being interviewed at the AGO as part of “Meet the Artist”. The AGO is also showing his video works from the acclaimed series Drawing Restraint. TIFF is presenting his films from The Cremaster Cycle, while his epic live-action film River of Fundament will be shown at the Elgin Theatre. A three-dimensional focus like this on a groundbreaking artist is a gift to the public. And then there’s Card Table Artifice. Famous British composer Gavin Bryars and sculptor-auditory artist Juan Muñoz created ten string quartet pieces with narration called A Man in a Room, Gambling, which premiered in 1992. They were inspired by card cheat S.W. Ernase’s 1902 book The Expert at the Card Table. Magician David Ben is taking it one step further. As the Art of Time Ensemble performs the music, Ben is demonstrating Ernase’s card shark tricks. Gavin Bryars will also be performing, and actor R.H. Thomson is the narrator.

Have you changed the festival at all? I am change itself because I am the programmer. The festival is going to reflect how I use the instruments to put together the orchestra. We have, however, had an important rebranding of the organization. We are now known as the Luminato Festival. The word “Festival” is now an official part of the name.

Does the programming have an inherent sense of balance? In effect, you are defining extremes. On one hand, there is the exclusive food and music experience, The Lost Train, that has an audience of eight in a secret location. And then there are the free events at the Hub which are open to everyone. There is also a balance between free and ticketed events, but this does not mean a divide between high and low art. I don’t believe in the existence of high and low art. There is only good art and bad art. The emphasis is on the experience for the audience.

You seem to be heading in a more experimental direction than in past seasons. I believe in taking the audience by the hand and leading them to new stuff, but we have to build up trust so they will follow. On the other hand, we also have to program the recognizable, like Pina Bausch, Daniel Lanois and the male duet evening put together by Rufus Wainwright. Another way of introducing the new and the different is taking a well-known personality like Isabella Rossellini, whose experimental theatre piece Green Porno will lead the audience into the unknown.

On the subject of Rufus Wainwright, is he in the festival because he’s your husband? The question has to be asked. Nepotism works if the idea is a good one. Rufus came to me first with the concept of If I Loved You: Gentlemen Prefer Broadway – An Evening of Love Duets. His twist was that these famous love songs from Broadway musicals would all be sung by and to men. He put the great line-up together – Boy George, Steven Page, Josh Groban and a host of others. It’s a unique concert. What was really funny is that the first four guys to confirm were all straight, so he had to find some gay singers. This is not a camp show. Rufus just wants the songs to be heard in a different way.

I’m pleased to see that there is more dance this season. I’m proud of this programming. On one hand we have the Pina Bausch company making its first appearance in Toronto in 30 years. She represents a dance heavyweight. We also have Louise Lecavalier, a great Canadian icon. Finally there is Lemi Ponifasio from New Zealand who is working with ten Maori women who are not trained dancers. They also sing songs of protest. He was inspired by the myth that a woman created the earth. The show is beautiful and moving. So we have old school, avant-garde and new world traditions.

Your association with the Toronto Symphony seems strong. For the third year in a row, they are giving the final outdoor concert at the Hub. In honour of the upcoming Pan-American/Parapan Games, the TSO will feature a travelogue of music from the Western Hemisphere. Their "TSO Goes Late Night" concert showcases Shostakovich's Symphony No.5.

Something new this season is The Copycat Academy. Can you explain this concept? I had the idea when I first came to the festival. It’s a project by Hannah Hurtzig from Berlin. Her field of expertise is modes of knowledge transfer. We had 70 applications from all over the world and accepted 20 participants from all fields and backgrounds. The academy is a week-long curriculum for emerging artists. We give them tools to grow in their art. This is a rethink about how artists are educated. You could call it a master class without a master. At the centre is a great artist to copy – and our first master is the Toronto-based artists’ collective General Idea who were pioneers of early conceptual and media-based art. The faculty helps the participants to deconstruct the themes of General Idea. It’s a parasitic relationship. By inhabiting General Idea, the students learn the tools of the master. Then they have to find their own voice. We’ve shown them the way up the mountain, but they jump off on their own. The audience connection is the evening talks that are open to the public.

After having this conversation with you, I’m coming away with the impression that you really want to instil a larger presence for the festival in the city. That’s true. Luminato is one festival of many forces, each pushing their own footprints. What I want is for people to say “I went to Luminato and saw such-and-such,” and not “I went to the Bluma Appel Theatre and saw such-and-such.” I want Luminato to be considered an indispensible part of this city – like TIFF is. I want the excitement about Luminato to wrap around Toronto. I want the taxi drivers and the kiosk owners to be proud of Luminato. I want to fill the name Luminato with emotion and meaning. I can feel that things are changing. We will get there.

Do you have any final remarks? The festival itself is a work of art.

The Luminato Festival runs from June 6 to 15. For details visit luminatofestival.com.

Paula Citron is a Toronto-based arts journalist. Her areas of special interest are dance, theatre, opera and arts commentary.