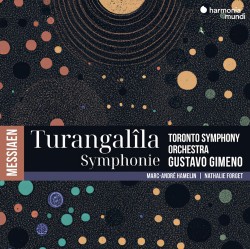

Messiaen – Turangalîla Symphony

Messiaen – Turangalîla Symphony

Marc-André Hamelin; Nathalie Forget; Toronto Symphony Orchestra; Gustavo Gimeno

Harmonia Mundi HMM 905366 (harmoniamundi.com/en/albums/messiaen-turangalila-symphonie/)

As I was preparing this review, I learned that the long-ailing Seiji Ozawa had died in Tokyo on February 6th at the age of 88. It seems a fitting memorial then in any discussion of this centennial celebration recording from the Toronto Symphony to also honour the legacy of the musician whom Olivier Messiaen (1908–1992) described as “the greatest conductor I have known.”

Messiaen’s monumental ten-movement hymn to love was commissioned for the Boston Symphony, by Serge Koussevitzky. Leonard Bernstein, filling in for an indisposed Koussevitzky, premiered the work in 1949, though he never recorded it himself. Among Bernstein’s many conducting assistants during his legendary tenure at the New York Philharmonic a young Japanese conductor by the name of Seiji Ozawa stood out. In 1965 Bernstein called TSO managing director Walter Homburger to recommend Ozawa as an ideal candidate to replace the departing Walter Susskind. Homburger eagerly signed him up and Ozawa soon rose to international prominence, culminating in his directorship of the Boston Symphony for an unprecedented three decades. He later confided in a 1996 interview with the Globe and Mail that “Every repertoire I ever conducted in Toronto, I did for the first time in my life – Tchaikovsky, Beethoven, Mahler, everything.”

Canada’s Centennial Commission saw fit to subsidize the landmark recording of Messiaen’s Turangalîla Symphony in 1967. It was a wise investment indeed. The acclaim this recording received promptly landed Ozawa, the Toronto Symphony and the composition itself firmly on the map of great performances. Subsequently the thoroughly hyped Ozawa eagerly suggested to Homberger that the TSO should stage a festival of Messiaen’s music. Alas, his proposal was summarily dismissed. For some reason Messiaen is a tough sell in Toronto; perhaps there is too much of a muchness about it all for some. I myself witnessed how the TSO audience trickled away in a 2008 performance (in the series “Messiaen at 100” – yet another centennial!) of this sprawling work under Peter Oundjian’s direction. Let us return to our recordings however.

In comparison to Gimeno’s bold and impulsive interpretation, Ozawa’s tempi for all ten movements are consistently fractionally slower than their modern counterpart by an average of 30 seconds. The analog sound of the era and the rich acoustic of the Massey Hall venue lend a welcome warmth to the sound – the bass register projects wonderfully. Our modern Roy Thomson Hall is comparatively weak at those frequencies but provides greater clarity for the often dense orchestral textures. This is especially notable in Gimeno’s superbly performed fifth movement whose complicated rhythms are dispatched at a blistering pace that would have been a severe technical challenge for the musicians of the 1960s. Kudos as well to the precision of the expanded percussion section, a sterling example of what a hotbed of the percussive arts Toronto has become.

It is also important to note that the performance is that of the revised orchestration of the work that Messiaen issued in 1990. The 2023 recording is mostly sourced from live performances and a patching session without, as far as I can tell, any digital jiggery-pokery from the Harmonia Mundi engineers.

The Ozawa performance (originally released on vinyl in 1968) was recorded under the supervision of Messiaen himself with Yvonne Loriod as piano soloist and her sister Jeanne Loriod playing the ondes Martenot. It was remastered for a Japanese CD release in 2004 on the RCA Red Seal label and is also available on a 2016 compilation disc from Sony (88875192952). Both TSO recordings are essential components in the discography of this seminal masterpiece of the 20th century.

Kamala Sankaram – Crescent

Kamala Sankaram – Crescent